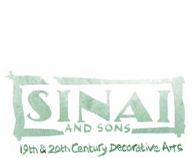

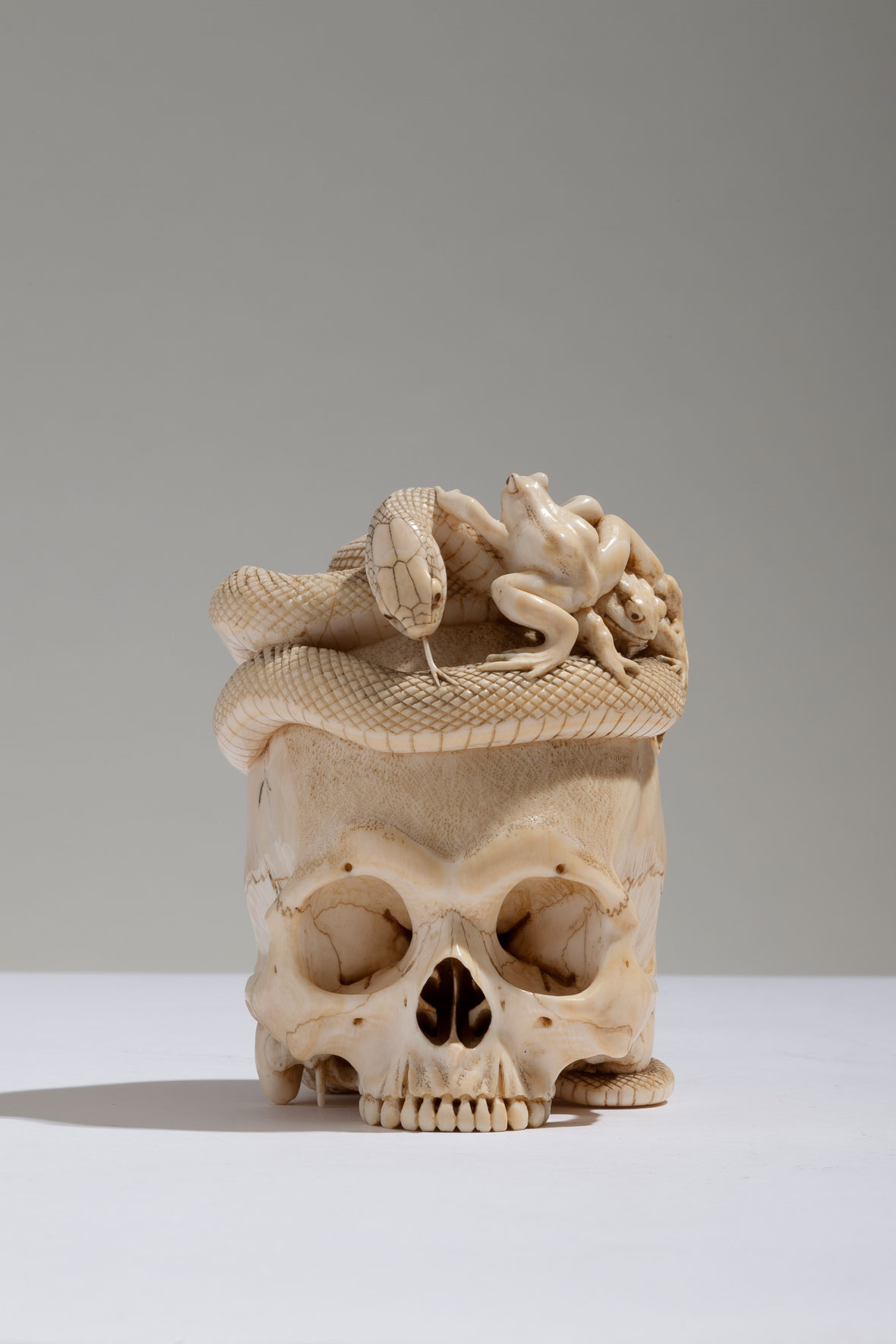

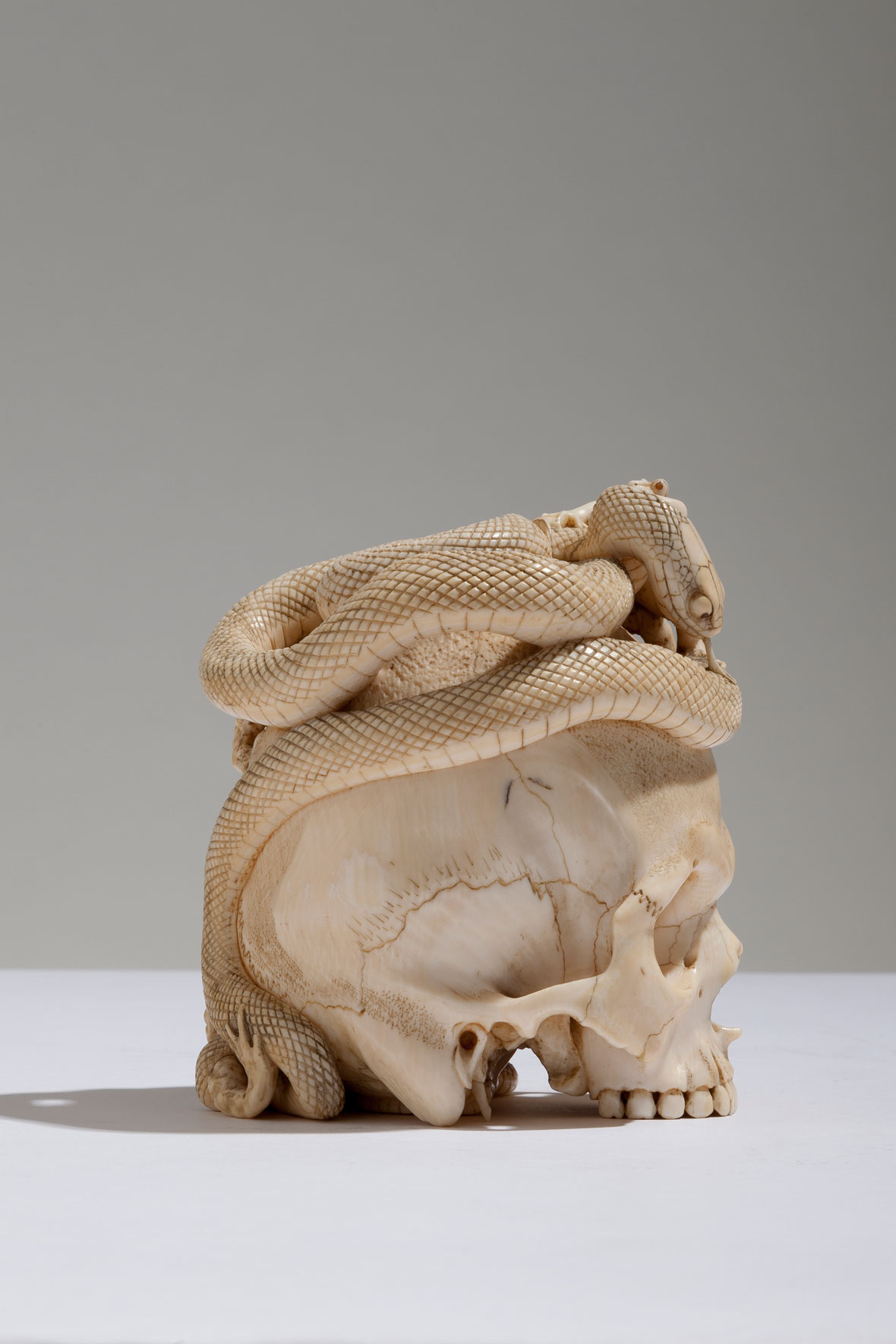

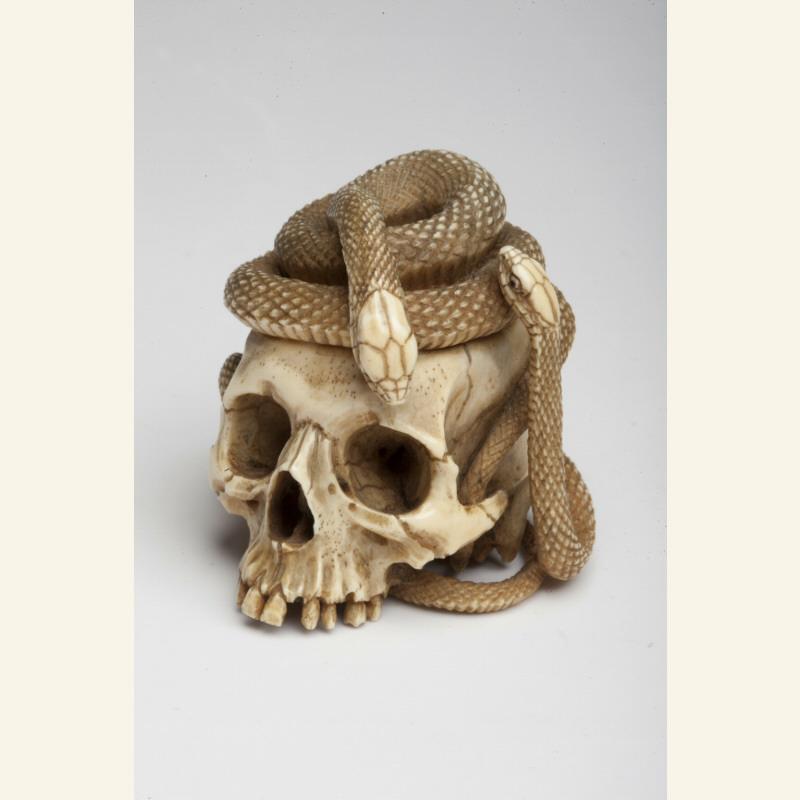

4 ¼ in (10.9 cm) high

Provenance

Private collection, UK

Literature

Okimono: Japanese Decorative Sculptures of the Meiji Period, Barry Davies Oriental Art, 1996, no. 12Before the Meiji Period (1868-1912) Japanese people had little tradition of displaying large decorative sculptures in their homes. Instead, the sculptures that they displayed in their Tokonoma (traditional display alcove) would have included Netsuke, which were smaller, less fragile, and also had a practical use. Decorative sculptures were almost exclusively confined to those of a religious nature and were carved for display in Temples. The earliest examples of decorative sculpture of a non-religious natured carved by Netsuke artists emerged in the late 18th and early 19th-centuries, and were presumably special commissions. The production of ivory okimono carved by Netsuke artists continued to increase into the early Meiji Period with more ‘finished’ exhibition-quality works of art. Netsuke artists who were known to have carved okimono of this nature, exclusively in ivory, include Sukenaga, the later generations of the Masanao family of Yamada, Ise, Hokyudo Istumin of Edo, and Sawaki Kihodo Masakazu of Nagoya.

The most famous of all okimono carvers was Ishikawa Komei (1852-1913). He was a court artist and member of the Art Committee of the Imperial Household. In 1891 he became a Professor at the Tokyo Art School, and his work and teachings influenced a new generation of sculptors, who concentrated exclusively on carving larger okimono. The finest artists of this School produced works of breath-taking quality and design in the late Meiji Period, of which this piece belongs to. Production was very limited due to the time necessary to complete these intricate sculptures – sometimes up to three years. The majority of these works were sold in the West, being proudly displayed in the Japanese pavilions of the great World Exhibitions of the time. Many were awarded medals for excellence.

The skull is regarded globally as a symbol of death. For the Western culture, ivory skulls as art objects would have been regarded as memento mori – literally a reminder of death and the shortness of life. A European example of a carved ivory skull with a snake, worms, toad and lizard, from the 17th-century, can be found in the British Museum. As in the West, the subject of the skull is one that has meaning and symbolism in Japanese sculpture and it was often portrayed in Japanese art of the Meiji period. The Japanese Buddhist symbol of Yama, the god of the dead, the skull is reminiscent of death but is also believed to be a sign of good luck, a charm to remind one of the transience of life. The Japanese are particularly fascinated by the supernatural and the after-life. A number of Japanese folktales, legends and ghost stories from the Edo and Meiji Period featured skeletons and skulls. With the skull being a popular symbol of the transience of life in Japan just as it was in Europe, these objects became highly sought-after in the West.

Similar works can be found in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, the Science Museum, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.